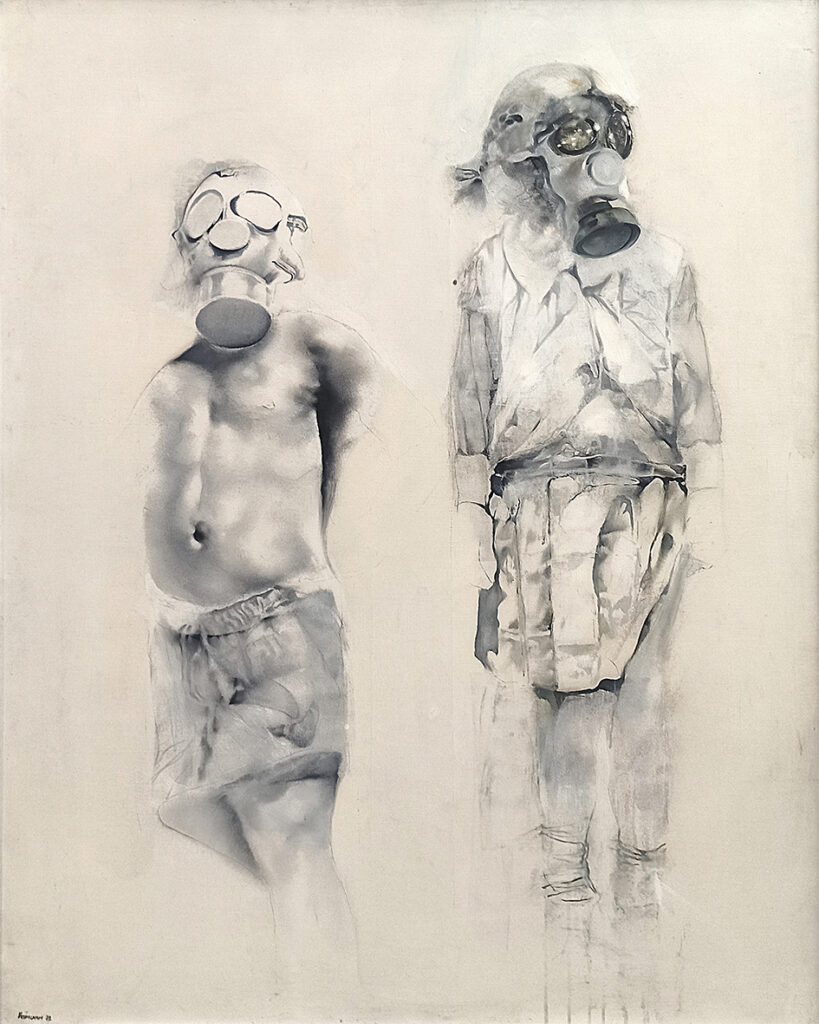

Ritengo che il momento più aulico della pittura sia stato il momento in cui l’artista, mosso dalla frenesia di una vita velata dall’insostenibilità del peso dell’esistenza, ha avuto il coraggio di utilizzare il mondo per raccontare se stesso. Sotto questa luce, alcune delle opere più famose di sempre, possono essere interpretate al di là di ciò che si vede per scendere nella profondità di ciò che si sente. Punto di partenza per tracciare questo percorso è la Canestra di frutta del Caravaggio, non solo la prima natura morta della pittura italiana, ma anche opera colma di significati che riflettono sulla caducità della vita. Le velleità umane, il carattere effimero dei beni materiali e la necessità di vivere secondo una morale integra rivolta ai veri valori della vita, trasformano questa natura morta in un’incredibile composizione ricca di simboli incarnati nella frutta e nelle foglie che stanno appassendo. Una vera e propria Vanitas che il Caravaggio dona al Cardinal Del Monte e che apre l’indagine ad una pittura che indaga gli insondabili segreti del nostro stesso esistere. Caravaggio ha vissuto la sua vita con la consapevolezza di un visionario; lontana dalla sublimazione del sacro, la sua pittura sconvolse committenti, pubblico, critici e colleghi con immagini di un realismo tale da non lasciare dubbi circa l’umanità delle sue figure. Invece d’innalzare lo sguardo dell’uomo verso il divino, le scene dipinte da Caravaggio portano il divino nel mondo degli umani: un mondo fatto di carne, di corpi e di muscoli, di piedi sporchi e di volti contratti in espressioni non sempre eleganti. Nei suoi vari autoritratti la luce mette a fuoco una pluralità di sfacettature della sua personalità, quasi fosse l’attore che recita le varie parti che gli vengono richieste dal copione. Con i riflettori puntati su se stesso, Caravaggio assume ora il ruolo del bacchino malato, ora quello del Golia decapitato, calandosi nelle parti identificando la propria anima con il rappresentato. Un mondo non troppo silenzioso nel quale il pittore racconta – non illustra – un infinito microcosmo di messaggi congiungendosi, nella linea temporale della storia dell’arte, nel momento stesso in cui assistiamo all’esasperazione espressa in un’opera come I mangiatori di patate di Vincent Van Gogh: ci troviamo al cospetto del puro stordimento esistenziale di un uomo incapace di trovare un senso alla sua stessa vita. Momenti privi di gratificazioni che si susseguono l’un l’altro gelando l’anima proprio come il freddo gela le dita di quei contadini dopo una lunga giornata passata nei campi. Raccolti attorno ad un tavolo a mangiar patate, questi uomini sono illuminati da una fioca luce, flebile come la speranza di sfuggire alla miseria che li circonda per raccogliersi attorno ad un attimo di pace dimentichi di tutto ciò che li aspetta al sorgere del sole. Gialli rancidi e verdi marci sono i colori dell’anima inquieta di Van Gogh, profondamente provata dai fumi della disperazione: non sono le mani di questi contadini ad essere gelate dal freddo, ma l’esistenza di un uomo inconsolabile che di li a poco troverà, nella Parigi impressionista, la speranza vana di un ritorno alla vita. I mangiatori di patate mi ricordano l’esistenzialismo profuso dalle opere di Alberto Sughi, così cariche di volti anonimi in preda al grigiore quotidiano che riempie stanze buie e umide cantine di paese. Un senso di accettazione della propria condizione che riflette un senso profetico e, allo stesso tempo, allusivo come una freccia impazzita di critica sociale con continui riflessi a città fumose e strabordanti di miasmi sociali. Sughi costruisce le sensazioni dell’Italia del secondo dopoguerra negli “anni della ricostruzione di un’identità post-bellica, affidata al recupero della “tradizione” – esemplificata dalla pittura seicentesca e da Caravaggio, oltre che dai primitivi italiani e i grandi del Rinascimento – per costruire un linguaggio “moderno”. Lo stesso farà Renzo Vespignani con maschere antigas, corpi diafani e volti contriti in un incessante confronto con quel fantasma “poetico” (come lo definì Rivosecchi) che lo ossessionò a tal punto da inchiodarlo nel tumulto di scenari terrificanti per mostrarci gli incubi e le follie di un’umanità che visse e subì l’orrore della guerra. Furono tutti artisti motivati da un profondo bisogno di libertà, di un linguaggio e di una poetica che li unì nel messaggio comune di rinascita. Come lo stesso Sughi ricorda in una lettera destinata all’amico Vespignani: “eri un ragazzo di vent’anni nel 1944, Renzo, quando il tuo sguardo si aggirava nei luoghi della periferia urbana, tra scali ferroviari, gasometri, case alveare e ne ricavavi disegni memorabili, significativi di un profondo malessere mescolato ad un ostinato vitalismo di un paese che in qualche modo ricomincia la sua storia”. Un Paese che, dopo l’incubo della guerra, si stava ricostruendo per la seconda volta, alla ricerca di un’identità e di un posto nel mondo. Così come la società anche l’arte ripartì e rispose ai vincoli imposti dal Regime per tornare finalmente alla libertà espressiva e gestuale.

I believe the most courtly moment of painting was the moment when the artist, moved by the frenzy of a life veiled by the unsustainable weight of existence, had the courage to use the world to tell about himself. In this light, some of the most famous works of all time can be interpreted beyond what is seen to descend into the depth of what is heard. The starting point for tracing this path is Caravaggio’s Canestra di frutta, not only the first still life of Italian painting, but also a work full of reflecting on the transience of life. Human ambitions, the ephemeral nature of material goods and the need to live according to an integral morality aimed at the true values of life, transform this still life into an incredible composition full of symbols embodied in the withering fruit and leaves. A real Vanitas Caravaggio gives to Cardinal Del Monte and opens the investigation to a painting exploring the unfathomable secrets of our very existence. Caravaggio lived his life with the awareness of a visionary. Far from the sublimation of the sacred, his painting shocked patrons, the public, critics and colleagues with images of such a realism as to leave no doubts about the humanity of his figures. Instead of raising man’s gaze towards the divine, the scenes painted by Caravaggio bring the divine into the world of humans. A world made of flesh, bodies and muscles, dirty feet and faces contracted in not always elegant expressions. In his various self-portraits, the light focuses on a plurality of facets of his personality, almost as if he were the actor who plays the various parts required of him by the script. With the spotlight on himself, Caravaggio now assumes the role of the sick bacchus, now that of the decapitated Goliath, descending into the parts identifying his own soul with what is represented. A not too silent world where the painter tells – he does not illustrate – an infinite microcosm of messages joining together, in the timeline of the history of art, at the very moment in which we witness the exasperation expressed in a work such as Vincent Van Gogh’s Mangiatori di patate. Here we find ourselves in the presence of the pure existential stupor of a man unable to find meaning in his own life. Moments devoid of gratification following each other freezing the soul just like cold freezes the fingers of those farmers after a long day spent in the fields. Gathered around a table eating potatoes, these men are illuminated by a dim light, as feeble as the hope of escaping the misery surrounding them to gather around a moment of peace forgetful of everything that awaits them at sunrise. Rancid yellows and rotten greens are the colors of Van Gogh’s restless soul, deeply tested by the fumes of despair. It is not the hands of these peasants that are frozen by the cold, but the existence of an inconsolable man who will soon find, in Impressionist Paris, the vain hope of a return to life. I mangiatori di patate remind me of the existentialism lavished by the works of Alberto Sughi, so full of anonymous faces prey to the daily grayness that fills dark rooms and damp village cellars. A sense of acceptance of one’s condition reflecting a prophetic and, at the same time, allusive sense like a crazed arrow of social criticism with continuous reflections on smoky cities overflowing with social miasmas. Sughi builds the sensations of Italy after the Second World War in the “years of the reconstruction of a post-war identity, entrusted to the recovery of the” tradition “ – exemplified by seventeenth-century painting and by Caravaggio, as well as by the Italian primitives and the great Renaissance – to build a “modern” language 1. Renzo Vespignani will do the same with gas masks, diaphanous bodies and contrite faces in an incessant confrontation with that “poetic” ghost (as Rivosecchi called him) that obsessed him to such an extent as to nail him in the tumult of terrifying scenarios so to show us the nightmares and follies of a humanity living and suffering the horror of war. They were all artists motivated by a profound need for freedom, for a language and a poetics that united them in the common message of rebirth. As Sughi himself recalls in a letter to his friend Vespignani: “You were a twenty-year-old boy in 1944, Renzo, when your gaze wandered around the places of the urban periphery, among railway yards, gasometers, beehive houses and you obtained memorable drawings, signifying a profound malaise mixed with an obstinate vitality of a country that somehow restarts its history”.2 A country that, after the nightmare of war, was rebuilding itself for the second time, in search of an identity and a place in the world. Just like society, art also restarted and responded to the constraints imposed by the Regime to finally return to expressive and gestural freedom.